How PBA Is Diagnosed

Pseudobulbar Affect (PBA) is typically diagnosed during a neurological exam by a specialist experienced in treating neurologic conditions or brain injuries. While there is no definitive test to diagnose PBA, doctors may use the Center for Neurologic Study-Lability Scale (CNS-LS) as a part of their evaluation. They will assess the patient and provide a diagnosis based on a thorough understanding of:

- Symptoms

- Medical history, especially the existence of a primary neurologic condition or brain injury

- Mental health history

- Findings from a physical exam

Learn more about what to expect and how to prepare with the Doctor Discussion Guide.

Getting a PBA diagnosis is not always straightforward

“Once you have a diagnosis …

from there, it gives you hope.”

— Liyah, caregiver for her mother, Sequena, a stroke survivor living with PBA

Individual results vary.

Finding a Specialist Who Can Treat PBA

Not all healthcare providers are familiar with PBA. If you think you could have PBA but have not yet been diagnosed, it's important to speak to a specialist who can diagnose and treat PBA. Below are 2 ways to find a specialist and schedule an appointment. Choose the option that works best for you and take the next step.

OPTION 2 Schedule an appointment with a telehealth specialist

If you prefer to make a virtual appointment, use this link to book a video visit with a specialist.

PBA May Be Difficult to Diagnose

Patients living with a neurologic condition or brain injury may find that the process of getting an accurate diagnosis for a secondary condition like PBA is not always straightforward. It’s not uncommon to feel emotional, tearful, stressed, or confused at times when dealing with the challenges of living with a neurologic condition or brain injury. Doctors may attribute the uncontrollable crying and/or laughing to mood changes or symptoms associated with their primary condition.

Not only do different patients experience PBA in different ways, but the episodes can also be difficult to understand and challenging to describe to a doctor. In addition, PBA is frequently mistaken for depression because of the overlap with symptoms of mood disorders and other conditions. All of these factors may complicate the diagnosis process.

The important thing to remember is that PBA is a separate neurologic condition of emotional expression that is caused by damage to the brain, and it can be treated.

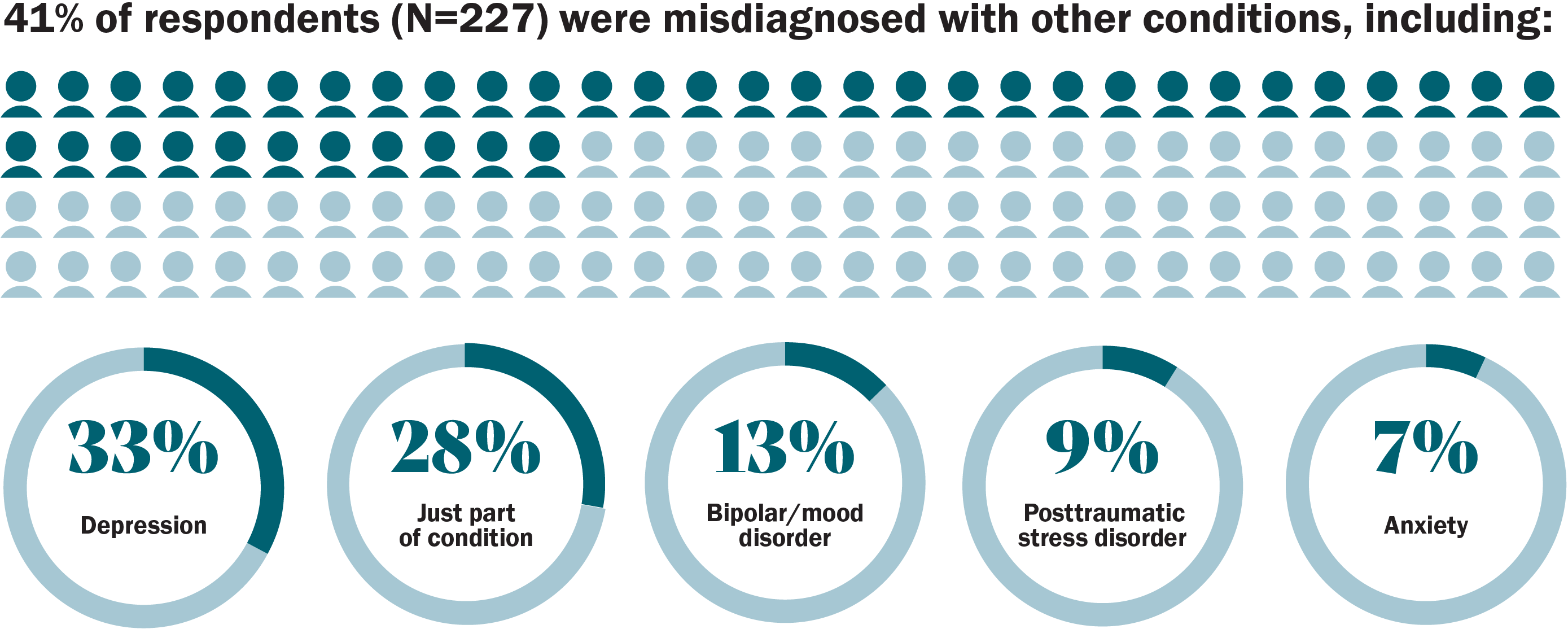

A Significant Portion of PBA Patients Are Misdiagnosed

An online survey of 637 respondents in the US who reported frequency of episodes suggestive of PBA* and discussed their episodes of sudden crying and/or laughing with a doctor found that:

*A CNS-LS score ≥13 is suggestive of PBA symptoms.

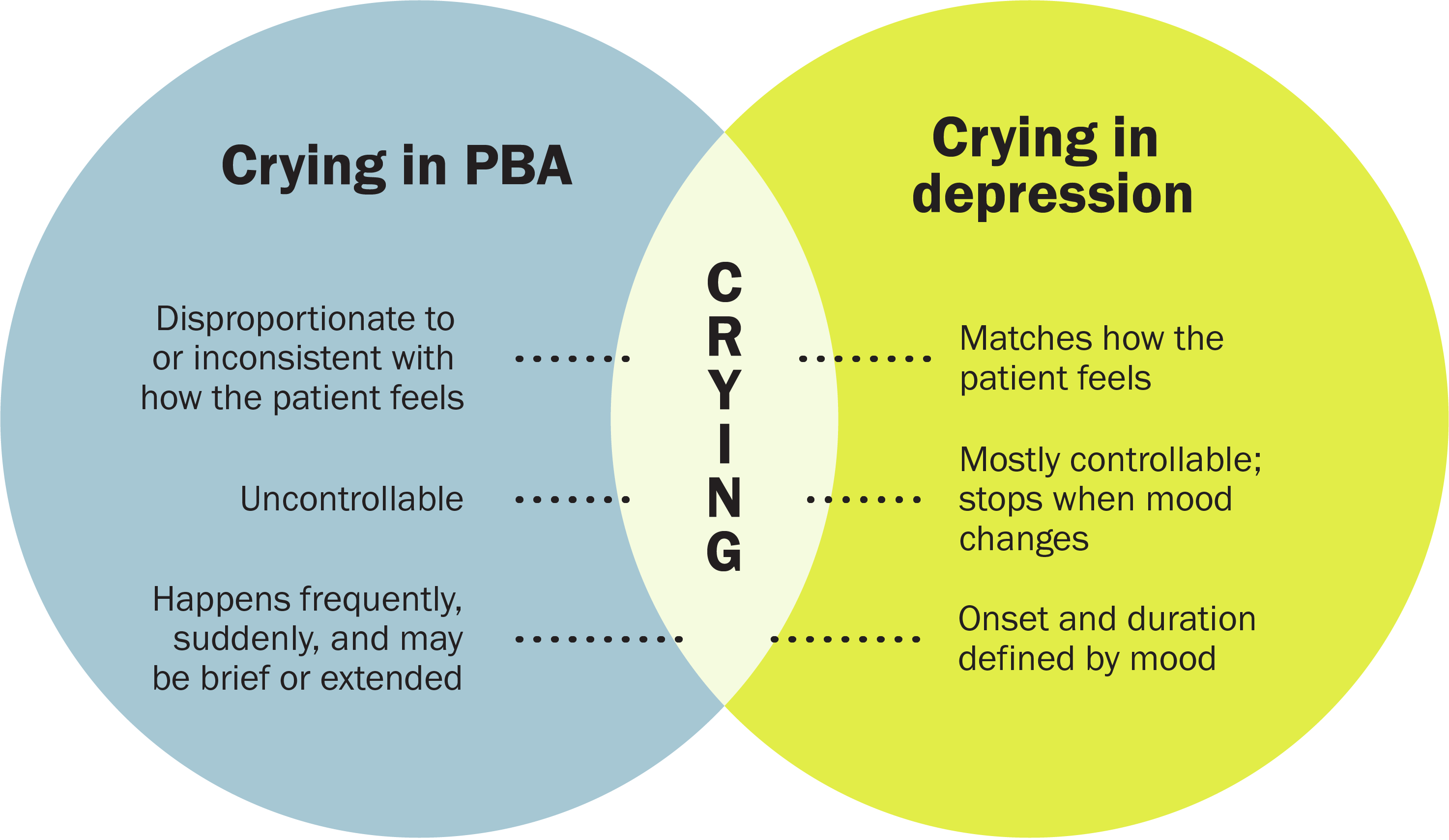

How PBA and Depression Are Different

Although PBA can be misdiagnosed as depression, remember that PBA and depression are separate and treatable conditions:

PBA

A secondary neurologic condition that causes involuntary, sudden, and frequent episodes of crying and/or laughing in people living with certain neurologic conditions or brain injury.

Depression

A common but serious mood disorder that causes severe symptoms that affect how a person feels, thinks, and handles daily activities.

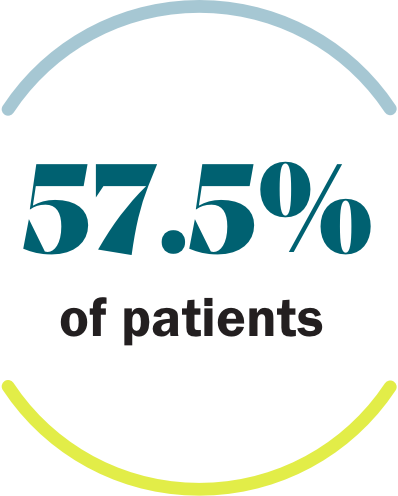

It’s common to have PBA alongside depression or other mood disorders. In a clinical study, over half of patients who were diagnosed with PBA also had depression.*† That’s why everything you discuss with your doctor is so important. It may take multiple conversations to get to the right diagnosis for you.

*PRISM II was a 90-day, open-label, single-arm, 74-site, US trial in adult patients with dementia, stroke, or traumatic brain injury. All patients received a clinical diagnosis of PBA by their physician and had a (CNS-LS) score of ≥13 at baseline. CNS-LS is a 7-item self-report rating scale that measures perceived frequency and control over crying and/or laughing episodes. It was validated as a PBA screening tool in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and multiple sclerosis populations. CNS-LS score of ≥13 may suggest PBA but does not confer a PBA diagnosis.

†Based on Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a 9-item assessment of depressive symptoms. Scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating increased depression severity.

“I was confused because [my doctor] was telling me that I had depression, and they were prescribing me antidepressants, but I was still crying uncontrollably all the time. So, I thought it had to be something else.”

Sequena, a stroke survivor living with PBA

Sequena is a real patient living with PBA. Image reflects patient with PBA at the time the image was captured.

Other Mood and Behavioral Disorders

Depression is only one of the mood disorders that has signs and symptoms similar to PBA. Crying is also common among other mood and behavioral disorders that people with primary neurologic conditions may experience, such as:

For instance, patients with traumatic brain injury may experience anxiety or posttraumatic stress disorder, and patients with dementia may experience delusions or other personality changes.

Sharing the details about your medical history, describing your symptoms in detail with examples, and sharing how you feel may help the doctor give you an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan.

Prepare for a Conversation With Your Doctor

What to expect before and during your appointment with your doctor.

The person depicted is not a real doctor.

It Could Be PBA.

Act Now.

The PBA Guidebook includes information on talking to your doctor about treatment for PBA. Request a copy by mail or download a digital version.

The person depicted is not a real patient.